Legends of the Nighthawks Diner

Simoncelli's Gilera 250 outside on the rear stand, popping as it idles.

by Dean Adams

Wednesday, March 22, 2023

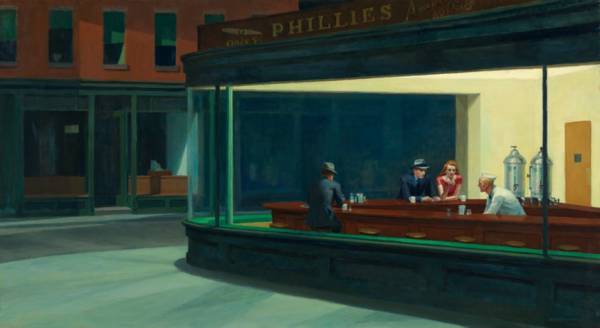

I'm not sure why, but when I see Ed Hopper's painting "Nighthawks," I think about Nicky Hayden and Gary Nixon.

Hopper's painting is, like any art, open to interpretation. Some people see it as a stark reality of lonely city life. Until I read that this is what it represented, I never thought of Nighthawks that way. I worked in a restaurant as a young person, and the people in that painting, to me, always looked like the bedraggled last bar-close type of customers or the sparse before-work crowd.

After Nick passed away, one of the few things I found solace in was the idea that he was in the hereafter with Nixon. And then, of course, Earl.

Earl Hayden was a good friend of Gary Nixon's. Nixon kind of muscled in when it came to mentoring the boys in racing. Sammy Tanner was the first one to make it into the OWB inner circle, but Nixon was Nixon, and he liked Earl and saw something in the boys he wanted to be a part of making. Nick used to say he fell asleep countless times on the floor of motel rooms with Earl and Nixon on the beds, Nixon telling stories one after another.

In my head, they are sitting together in that Hopper's infamous diner, late at night. Nick is—maybe—drinking coffee, and Nixon is beer-buzzed with one in front of him. Two motorcycles are parked outside: a Triumph for Nixon on the sidewalk. It would be leaning against the wall because, like most guys his age, Nix had some contempt for street bikes, calling them "fuggin kickstand bikes" or something like that. Nick's ride would be his RC51 Superbike, parked haphazardly on the sidestand on the street.

(Nicky and I talked about building some kind of RC51 street tracker after he finished racing, but I always suspected that inevitably it was going to be a Honda RS750 'cause that was his favorite bike after his RCV212 V5 GP racer. He liked the RC51 but never really showed too much desire in having one until late in life.)

Art critics and enthusiasts have varied opinions about "the third man" in Hopper's painting, the man sitting alone at the bar with his back to the window. Clearly, he is some kind of contemporary to the other inhabitants inside the diner; he knows of their life, they are together inside the cafe but at the same time still separate.

So, if it's Nixon and Nick facing the window, who is it that is facing them in the racing version of "Nighthawks"?

I've always thought it might be Sic. He went first, of course, and I'm not sure he and Nicky knew each other very well. Nixon not at all. So they are together and separate there, in the dark, waiting for the sun to come up so they can ride. Simoncelli's Gilera 250 outside on the rear stand, popping as it idles.

I found this old story of Nick talking about Nixon a few days ago on an old computer:

(2011)

To Americans of a certain vintage, the name “Nixon” conjures up immediate mental images. For mainstream America, it’s a desperate man doing an odd, shuddering peace-sign jig in front of a helicopter parked on the White House lawn. For American racing enthusiasts, the mental image is one of a man of nearly unbreakable will and spirit, a man known for deed and exploit, a legend. That man is Gary Nixon, motorcycle racer. Nixon died of heart failure on August 5th 2011, closing the book on a 70-year-old racing legend.

A two-time national champion in 1960s AMA racing—when the class tallied both roadracing and dirt track results for one championship—Nixon was recognized as a rider that only death could stop. His list of racing injuries almost meets or exceeds his contemporary, ‘70s showman and motorcycle stunt man Evel Knievel. Broken legs, double-broken arms, a smashed back, and shattered feet all earned in racing spills from California to Japan and back. These and more were the scars that Nixon accumulated, along with the trophies, factory contracts and countless stories of epic proportion. Nixon won at Daytona on a Triumph, lost a politically charged world championship on a Kawasaki, crashed a Suzuki in Japan so hard that it almost ended his career and left the motorcycle a reputed 21 feet in the air, still hanging in a tree.

In a way, Nixon was racing’s Elvis in 1956, a person who changed everything. Perhaps he didn’t change the way that motorcycles were raced, but he changed the way motorcycle racers went about their business, both on and off track. He didn’t blindly follow rules of the sanctioning body, and he never patted someone on the back for a job well done if they hadn’t earned it. Nixon was infamous for not leaving his house to race motorcycles if he wasn’t being compensated for it, and that was a major influencer in the factory contracts that riders started signing in the 1970s—contracts with a great number of zeros on them.

“It’s easy to say that there will never be another Gary Nixon,” says 2006 MotoGP champion Nicky Hayden, who counted Nixon as a close friend and hero. “But I don’t think that there was ever a racer like Nixon before him, either. In so many of the stories he’d tell, the main point was that, when he did something, people acted like this was the first time they’d ever seen anyone do that.”

Hayden saw just that when Nixon, then 65 years old, stopped in Owensboro and found the Hayden brothers lapping on their oval practice track one afternoon. He watched the trio slide around the track on off-road bikes for a while, and then decided to join in.

“He had a pair of motocross boots that he pulled on,” says Hayden, “but he didn’t like the way they felt with a steel shoe on the inside boot. So he stopped, pulled the boots off, slipped his Nike tennis shoes back on, tied the steel shoe to that, and then went back out. He was not slow by any means, but I can remember following him, seeing that left foot come out and on it was a Nike and a steel shoe. I’d never seen anyone do that before. I just laughed and shook my head. Only Nixon!”

Hopper's painting is, like any art, open to interpretation. Some people see it as a stark reality of lonely city life. Until I read that this is what it represented, I never thought of Nighthawks that way. I worked in a restaurant as a young person, and the people in that painting, to me, always looked like the bedraggled last bar-close type of customers or the sparse before-work crowd.

After Nick passed away, one of the few things I found solace in was the idea that he was in the hereafter with Nixon. And then, of course, Earl.

Earl Hayden was a good friend of Gary Nixon's. Nixon kind of muscled in when it came to mentoring the boys in racing. Sammy Tanner was the first one to make it into the OWB inner circle, but Nixon was Nixon, and he liked Earl and saw something in the boys he wanted to be a part of making. Nick used to say he fell asleep countless times on the floor of motel rooms with Earl and Nixon on the beds, Nixon telling stories one after another.

In my head, they are sitting together in that Hopper's infamous diner, late at night. Nick is—maybe—drinking coffee, and Nixon is beer-buzzed with one in front of him. Two motorcycles are parked outside: a Triumph for Nixon on the sidewalk. It would be leaning against the wall because, like most guys his age, Nix had some contempt for street bikes, calling them "fuggin kickstand bikes" or something like that. Nick's ride would be his RC51 Superbike, parked haphazardly on the sidestand on the street.

(Nicky and I talked about building some kind of RC51 street tracker after he finished racing, but I always suspected that inevitably it was going to be a Honda RS750 'cause that was his favorite bike after his RCV212 V5 GP racer. He liked the RC51 but never really showed too much desire in having one until late in life.)

Art critics and enthusiasts have varied opinions about "the third man" in Hopper's painting, the man sitting alone at the bar with his back to the window. Clearly, he is some kind of contemporary to the other inhabitants inside the diner; he knows of their life, they are together inside the cafe but at the same time still separate.

So, if it's Nixon and Nick facing the window, who is it that is facing them in the racing version of "Nighthawks"?

I've always thought it might be Sic. He went first, of course, and I'm not sure he and Nicky knew each other very well. Nixon not at all. So they are together and separate there, in the dark, waiting for the sun to come up so they can ride. Simoncelli's Gilera 250 outside on the rear stand, popping as it idles.

I found this old story of Nick talking about Nixon a few days ago on an old computer:

(2011)

To Americans of a certain vintage, the name “Nixon” conjures up immediate mental images. For mainstream America, it’s a desperate man doing an odd, shuddering peace-sign jig in front of a helicopter parked on the White House lawn. For American racing enthusiasts, the mental image is one of a man of nearly unbreakable will and spirit, a man known for deed and exploit, a legend. That man is Gary Nixon, motorcycle racer. Nixon died of heart failure on August 5th 2011, closing the book on a 70-year-old racing legend.

A two-time national champion in 1960s AMA racing—when the class tallied both roadracing and dirt track results for one championship—Nixon was recognized as a rider that only death could stop. His list of racing injuries almost meets or exceeds his contemporary, ‘70s showman and motorcycle stunt man Evel Knievel. Broken legs, double-broken arms, a smashed back, and shattered feet all earned in racing spills from California to Japan and back. These and more were the scars that Nixon accumulated, along with the trophies, factory contracts and countless stories of epic proportion. Nixon won at Daytona on a Triumph, lost a politically charged world championship on a Kawasaki, crashed a Suzuki in Japan so hard that it almost ended his career and left the motorcycle a reputed 21 feet in the air, still hanging in a tree.

In a way, Nixon was racing’s Elvis in 1956, a person who changed everything. Perhaps he didn’t change the way that motorcycles were raced, but he changed the way motorcycle racers went about their business, both on and off track. He didn’t blindly follow rules of the sanctioning body, and he never patted someone on the back for a job well done if they hadn’t earned it. Nixon was infamous for not leaving his house to race motorcycles if he wasn’t being compensated for it, and that was a major influencer in the factory contracts that riders started signing in the 1970s—contracts with a great number of zeros on them.

“It’s easy to say that there will never be another Gary Nixon,” says 2006 MotoGP champion Nicky Hayden, who counted Nixon as a close friend and hero. “But I don’t think that there was ever a racer like Nixon before him, either. In so many of the stories he’d tell, the main point was that, when he did something, people acted like this was the first time they’d ever seen anyone do that.”

Hayden saw just that when Nixon, then 65 years old, stopped in Owensboro and found the Hayden brothers lapping on their oval practice track one afternoon. He watched the trio slide around the track on off-road bikes for a while, and then decided to join in.

“He had a pair of motocross boots that he pulled on,” says Hayden, “but he didn’t like the way they felt with a steel shoe on the inside boot. So he stopped, pulled the boots off, slipped his Nike tennis shoes back on, tied the steel shoe to that, and then went back out. He was not slow by any means, but I can remember following him, seeing that left foot come out and on it was a Nike and a steel shoe. I’d never seen anyone do that before. I just laughed and shook my head. Only Nixon!”

— ends —